This series of artworks incorporates living creatures in the paint of watercolor paintings. I do not know of anyone else who has purposefully put living creatures in the paint of their paintings, with the intent of keeping them alive in the paint. (Although Salvadore Dali used live snails as part of his “Rainy Taxi” sculpture, and Banksy painted an entire elephant as part of “Barely Legal.”) Lots of bugs and pollen and other creatures and organic matter have gotten stuck in paintings while they were being made, of course. But that’s not the usual intent of the painter.

Plein Air Painting with Local Water

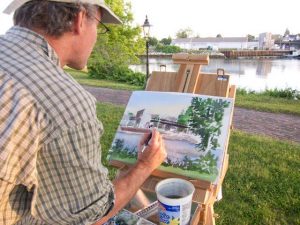

I’ve always enjoyed painting outdoors. (See my article “The Nature of the Plein Air Artist” in 2018’s The Art Guide.) I often use water from a nearby marsh, river, puddle, or ocean to mix up the paint. Just to make the painting more of the place. We paint outdoors to better capture nature, right? So why not put a little something of nature in the painting? Also, I like to emphasize that my paintings are physical objects, rather than just another of the countless images we are bombarded with every day. Including local water in my watercolors makes them somehow more physical, more like flat sculptures than images.

Most any water found outdoors has many tiny living things in it. So I’ve already made lots of paintings with tiny creatures in the paint. I imagine that, at some time in the distant future, given sufficiently sophisticated analysis, the locale in which my paintings were made could be identified.

Come to think of it, a huge number of plein air painters throughout history—perhaps most of them—must also have used water with living creatures in it. Because most watercolorists just wouldn’t have carried tap water out into the country to paint.

Tardigrades: Dormant in the Paint

But this past summer when I was out at Shoals Marine Laboratory (SML) on Appledore Island as Artist in Residence I began to put specific living creatures in my paint, with the intent of keeping them there, alive. The idea was sparked by Dr. Jennifer Seavey, Kingsbury Executive Director of SML, who mentioned that tardigrades (a.k.a. “waterbears” or “moss piglets”) could be harvested from the orange lichen on the big tower on Appledore.

(Tardigrades are very small, almost-microscopic animals that are known for their ability to adopt a dormant state and survive in extreme and unusual conditions. They have been revived after being dried out and dormant for over 100 years. There are over a thousand species of tardigrades, ranging in size from about a quarter of a millimeter to one millimeter in size. They live in mostly aquatic environments almost everywhere on earth. They have eight stubby little legs which they use to paddle around with. They mostly eat plants and algae. Here’s a good video if you’d like to learn more about tardigrades.)

So, with the help of Taylor Lindsay and Madeline Young at SML, I made a little strainer apparatus and soaked some lichen and filtered out some tardigrades. I’ve put them in a couple paintings so far. Here is the first one (click on the image to see it bigger):

The tardigrades in the paint of this painting are not visible, nor do they affect the appearance of the paint. The tardigrades-in-water sample (which I add a few drops of to the paint) does smell a bit, well, “swampy.” (Note that my “tardigrade” water sample actually includes many other tiny creatures that were harvested from the lichen at the same time.)

The intent for these paintings is that the tardigrades in the paint will become dormant and survive for many years on the paintings. In a few years I intend to wash the tardigrades off a painting or two and revive them.

Trematodes: Paintings Become Another Host in the Parasite’s Lifecycle

Then, while still out at SML last summer, I was talking with parasite expert and SML Scientist in Residence Dr. Carrie Keogh of Emory University. She said she could isolate some trematode eggs that I might want to put in my paintings. Trematodes are parasitic flatworms common on Appledore Island. Their lifecycle goes from birds to snails to fish and back to birds.

Then I thought, “Hey, if we could get the snails infected by way of the paintings, then the paintings would become one more host in the trematode lifecycle!”

Here’s the painting as I was painting it (click on it to see it bigger):

Here’s Carrie in the lab:

And here’s a video of the same painting with trematode eggs on it and a snail crawling across them: “Appledore Apple Tree Watercolor with Trematode Eggs and Snail, by Bill Paarlberg and Carrie Keogh.”

Here’s the painting hanging at the York Public Library show (click on it to see it bigger):

As with the tardigrade paintings, the trematode eggs don’t affect the look of the paint. They were visible as tiny specks when they were on the painting, and after the snails crawled across them, some of the specks were gone. So we are pretty sure the snails picked them up. We are still waiting to see if the snails have actually become infected. Dr. Keogh has several ideas as to how to increase the odds of snail infection for future projects, including putting the trematode eggs in a substance that the snails like to eat.

It seems to me that one next logical step here is to bypass the painting-on-paper part of this project, and do a painting right on the rocks outdoors. Instead of doing a painting of the rocks, do the painting on the rocks. Preserve the painting with some kind of non-toxic weatherproof sealant, and then put the trematode eggs right on the painting on the rocks. (And in this case “trematode eggs” means “bird poop” because that’s how they come out of the birds. And, come to think of it, “rocks” in this case would probably mean something flat-ish, portable, and not necessarily actual native rocks, but maybe flagstone or similar.) Then the snails can find the painting and the eggs as part of their natural habitat, instead of in the lab. Perhaps a project for next summer.

###